In Memphis they’re pressing hard against their food problems.

At least 30 percent of adults were obese in thirteen states including Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi and Tennessee. The same four states led the country in the rates of diabetes. Food deserts are pervasive in rural Delta areas according to a study by Mississippi State University.

At the same time, organizations such as the Healthy Memphis Common Table are facilitating Famers’ Markets to help them accept SNAP benefits and offer dollar-matching programs. The non-profit Grow Memphis is securing funding and starting community gardens in some of the poorest parts of the city. The Green Machine is bringing fresh foods in a mobile food market to public schools, community centers, and senior citizen facilities.

The head of food services for the public schools has created a farm-to-school program, started an after-school supper program, expanded the breakfast program and used the department’s huge central kitchen to return to scratch cooking. He’s started more than 20 school gardens and more are on the way.

The culinary director at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital has radically re-oriented the food service programs toward local sourcing. He and the team that feeds St. Jude represent a new generation of trained chefs who apply the ethic of fresh, locally grown, healthier food to a large, international hospital. Today, nearly 40 percent of what’s cooked is locally grown and represents about a $1 million annual economic boost for the region.

This news should be shared widely in an area that continually ranks as one of the unhealthiest in the country.

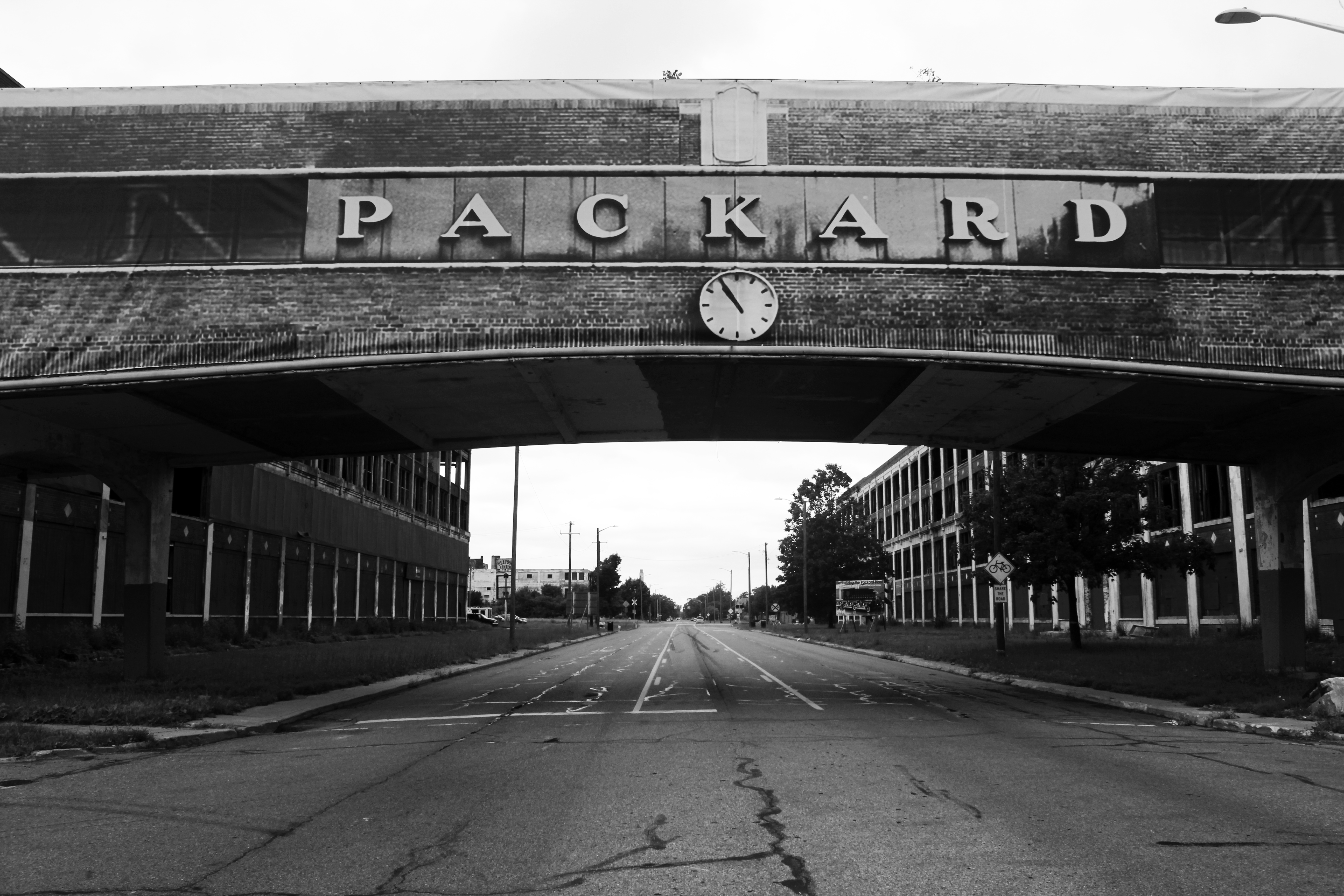

The energy funnel narrows in the Mid-South. The region is a web of pipelines, heavy rail and interstates with the Mississippi River running right through the middle. The explosion in new extractive technologies is flooding aging infrastructure, stressing pipelines and rail cars with products more volatile and harder to remedy than conventional oil.

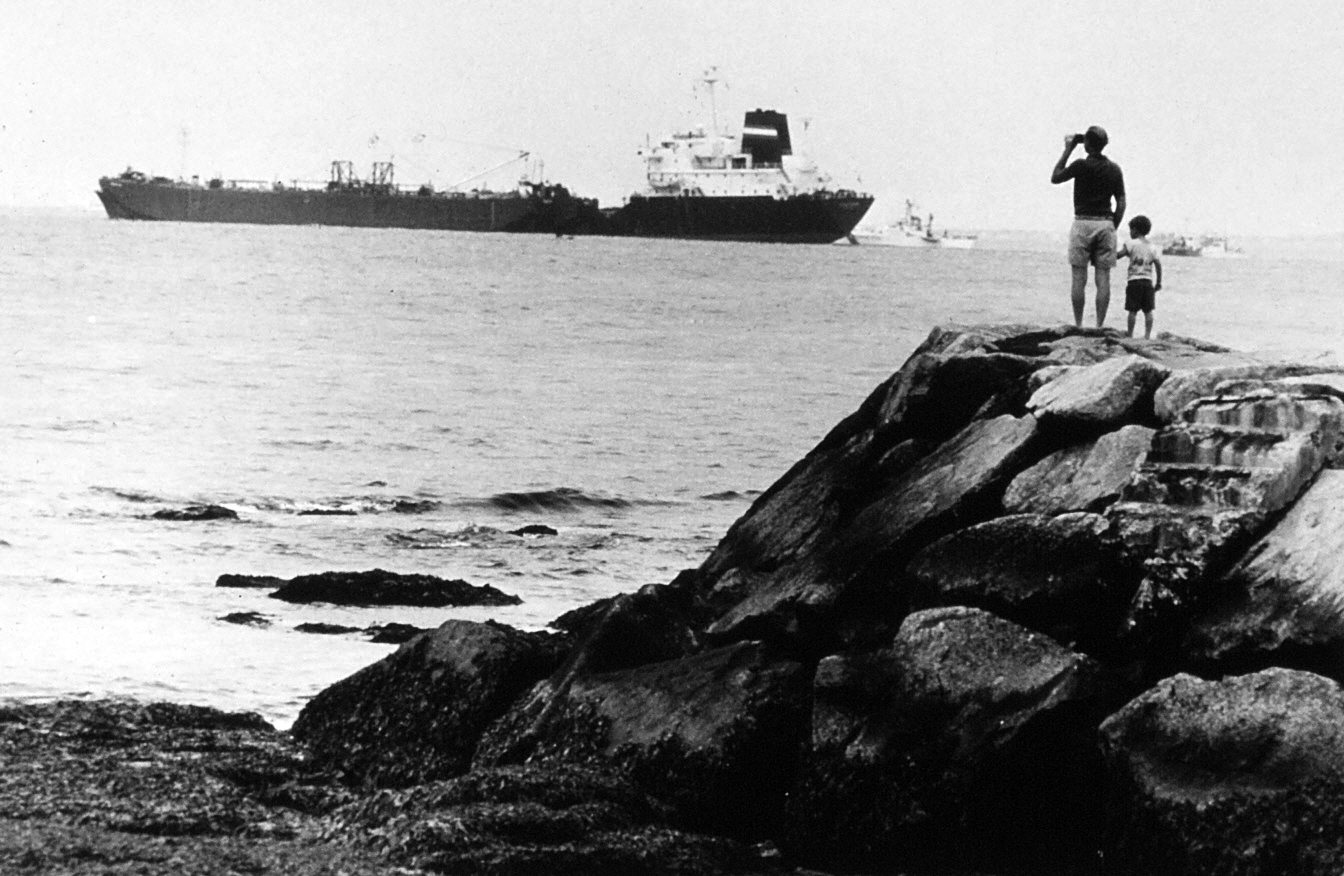

When a repurposed, 60-year old, pipeline ruptured in Mayflower, Arkansas, it spilled thousands of barrels of diluted bitumen (tar sands oil) into a stream feeding a popular recreational lake. First responders and residents were sickened and fresh water was fouled. Two hundred miles to the east, the Memphis newspaper relied on wire reports scattered throughout its editions. There are currently pipelines running through Memphis that are now in the repurposing and permitting process but aren’t reported by local news outlets..

When twenty-five oil tanker cars went off the tracks in Aliceville, Alabama, it set off an inferno that could be seen from 10 miles away and polluted tributaries to the Tom Bigbee River system. News outlets in Little Rock and Memphis again relied on wire reports and could not determine the volume of oil transported by rail through Tennessee or Arkansas, the energy logistics hubs of the South.

When the walls of a dam holding 1.1 billion gallons of coal ash crumbled in Kingston, Tennessee, it spilled toxic sludge over 300 acres in the largest industrial spill in U.S. history. The wave of ash wiped out roads, crumpled docks and destroyed homes. News outlets in the region published wire reports without making mention of the coal plants in Memphis and just upriver in Osceola, Arkansas. Three years after the spill the Environmental Protection Agency has little regulatory authority over coal ash and a bill proposed by a bipartisan coalition of coal-state senators would strip away the federal government’s power to do anything about it.

What happens in Arkansas matters in Tennessee and Alabama and Mississippi. Yet there is no organized communication network between them. The common thread is that all of those who have been affected feel driven to share their experiences. Those who might be affected in the future want to know what questions to ask, how to protect their rights and what resources are available to force the best environmental remediation possible.