Scott Sines, ©Green Rocket News

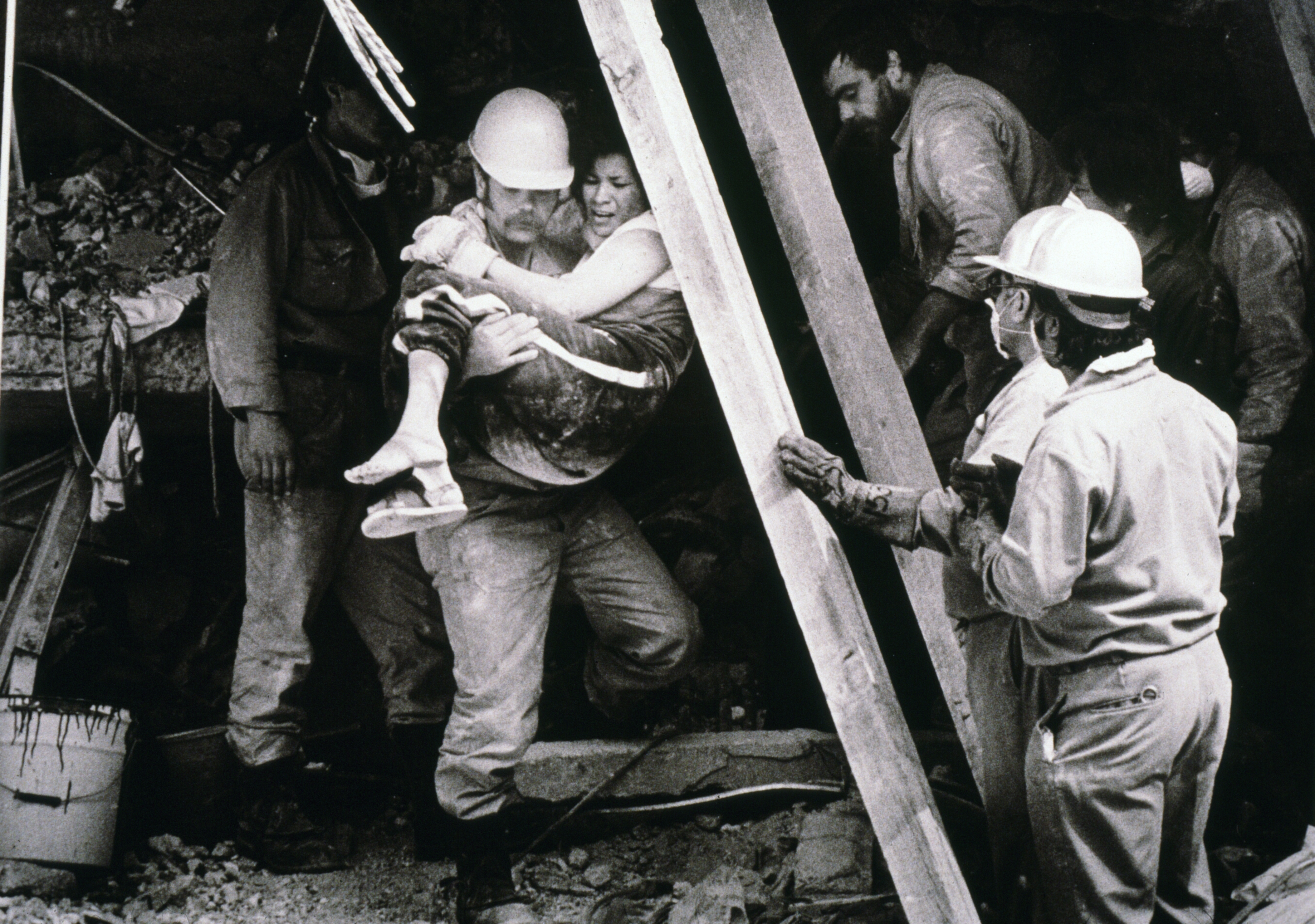

Craig Ritter marches through chest high reeds toward ground zero of the largest inland oil spill in U.S. history. Suddenly he sinks calf-deep in an oily bog. A petroleum odor releases immediately. “This all used to be a pond,” he says, as he uses a rake and potato fork to extricate himself.

Meanwhile, Enbridge Inc. is stomping on the gas.

Marathon Oil just spent millions to increase its dilbit refining capacity in Detroit and it’s hungry for more dilbit.

The company needs to pump more dilbit as fast as it can. While Line 6B was repaired after the catastrophic 2010 spill in Marshall, Michigan, it has been operating at eighty percent capacity. Losing real money, and potential increased revenue, everyday.

Enbridge knows Line 6B needs to be replaced. Documented cracks put it at a higher risk for rupture.

They also know capacity needs to increase. But the company can’t stomach the lengthy permitting process that comes with new international pipeline construction (Keystone XL). It has presented its newer, bigger pipelines, in segments, as repair and replacements, under the existing permits. It’s faster and cheaper.

Adding urgency is The Pipeline Safety Act of 2011. Enacted mainly in response to the Marshall spill, there has been little new rule making. Recently, Democratic Rep. John Dingell sent a letter to the Secretary of Transportation arguing that new regulations are “taking far too long.” New regulations can only slow the company down. There is money on the table.

.

hello.

Comments are closed.